- Home

- Brand Gamblin

Tumbler Page 6

Tumbler Read online

Page 6

She could hear Joey, muffled in the stall next to her, "Well, you are pretty consistently late for work."

She scowled, "When I'm late, I put in overtime. Nobody can ding me for that."

She could almost hear him shrug, "I guess, but he's got quotas and machine rental and stuff like that."

"So what are you saying? I owe him some special loyalty for giving me the privilege of coming in to work? If he's got a problem, he can kiss my pearly white ass."

"I'm just saying that you may be ticking him off for no good reason. I mean, why would you be late for work? It's not like you've got a really active social life or anything."

Libby stopped scrubbing suddenly. That one hit a little too close to home. She scowled through the floating lather. "I do my work, that's the important thing."

"I dunno. It wouldn't kill you to get along with the other guys here. Maybe that's the problem. Showing up on time, not being such a . . . well not being so hard on everybody. Maybe if you just acted like you liked the job a little bit -"

Libby slammed her fist into the shower drain button, "Yeah? Well, maybe I don't like the job at all. Maybe I don't like being a freaking slave.” Jets from above whirred into life as they sucked the lathered water out of the shower stall, drying her as it cleared the room.

She coasted out of the stall, grabbing her towel as Joey started to protest, “Hey, it's not like that, Tumbler. Everybody works for a living. I'm just saying -”

"Well, thanks for the pep talk, Joey. Maybe next time you can teach me which fork to use at dinner."

She could hear Joey saying something in defense, but she didn't want to listen. She dried off, slipped into her clothes and environment suit, and sailed out the door.

Inside the suit, she sighed and fogged up the visor. She sailed over to the executive trailer, and thought about knocking on the door before cycling it. She raised her hand, then thought better of it. It just seemed too juvenile to play at.

She cycled through the door, and faced her boss. Libby removed her helmet and saw him sitting at the desk, grappling with an estimate adjustment form.

He didn't look up, "If you don't intend to shape up and start doing a better job, I mean this instant, then you can just put that helmet back on and walk."

"Shape? What do you mean, shape up? I'm the best digger you've got out there!"

He looked up finally, a mixture of guilt and anger on his face.. Bronson wasn't a bad sort, for a boss. He was a tall, thick man, who didn't look like he belonged behind a desk. A bushy mustache turned down the sides of his mouth so that he always seemed to be frowning. He never shouted, never seemed to be angry at her. He just never seemed to be pleased with her, either. He nodded, "Yeah. You do all right, when you're alone, but that's not the kind of worker we need here."

She scowled at him, "Exactly what kind of worker does a mining corporation need, if it's not a good digger?"

He took a deep breath and put his pencil carefully into it's clasp on the desk. "Carter, you do a good job when you're working alone. You turn up good results on digging the furrows, and you do all right at breaking off the furrows, but when it comes to rarefying or analyzing ore, you just don't show up."

She puffed out her cheeks and rotated slowly in place, "It's a bunch of eggheads sitting around a computer, getting all giddy about 0.03% of this, or 0.05% of that. You run it through the computer, pick the biggest number, and say 'That's it!'. I don't need to stick around for that."

"That's not your call, Carter."

She shrugged, a gesture which was barely noticeable in zero G. "Besides, I've been here long enough to know one rock from another. Gimmie a sample, I'll tell you what the majority percentage is."

He shook his head, "There's more to it than that, and you know it. If there's one hundredth of a percent of platinum in an iron sheet, you don't just call it an iron sheet. You'd melt out all the iron, and throw it away if that's what it took, because the platinum is worth thousands of times what the iron is worth. The goal isn't to find the greatest percentage. It's to find the greatest value."

She started looking around the room, projecting boredom, and took a deep breath. "When you first got here, you took an interest in all this. You showed real promise, across the board."

She turned to face him, biting back her words. She remembered that all too well. When she first got there, she had been scared. She'd been shanghaied. Dropped on a pebble with a shack, and told that she had to work for someone else, just to survive. She would have done anything, studied her heart out, just to keep food money coming. Well, she'd studied, she'd learned, and she knew the job. She knew how much she had to do to keep them from firing her.

She held her tongue and stared back at him. After a moment, she said, "Okay. So, understood Cap'n. Thanks. Lesson learned. I've got a lot to think about, so why don't I just go do that?"

Bronson moved away from the desk, advancing on her. "Make no mistake, Carter. I want to keep you here. I think you have promise, and we need workers. But if you can't work with others, we'll just have to find a way to get along without you."

She looked away, then bounced over to the door, before she could say anything else. Once she was outside, at the group vehicle tether, she sat down on her runabout and fumed.

She hated feeling this way. She hated being angry all the time. She wasn't like this, normally. It had just been so long, so much hard work. She was even shouting at Joey, and he didn't deserve that. Of everyone here, he was the one who understood her the most. Joey was trapped in the same setup she was, assigned to the tumbler rock just a year earlier than she was. He had just enough money on him to rent out a place on Ceres, so he was able to start working in relative comfort. But even Joey felt what it was like to be trapped out here. He knew what it was like to be alone and in hock for your freedom. She shouldn't be shouting at him.

It was just this place. This horrific life, where they take everything away from you, force you to work for them, then tell you to be happy about it. It just wasn't fair.

She kicked the runabout into gear and headed back to her shack. It didn't matter anyway. Today was the big day. After this, none of them would matter any more.

As she sailed back to her rock, she passed one of the larger estates. It was the Davis claim, a gypsum conglomerate that was so random, different sections could hold almost any kind of ore. As she passed, she saw the two Davis children, Dora and Mike, surveying the furrows. They waved at her, and she half-heartedly waved back. Mike was the first kind soul she'd met in this hellhole. At least, he knew the score and felt bad about it when she found out about the shack. And Dora had always been helpful with learning about mining. Even though she was only ten years old, she had seen more surveys and had overseen more mining than Libby ever had. Dora had an encyclopedic knowledge of rock types, and a passion for rock collecting. If it weren't for Dora, Libby knew she never would have got her ranking. Libby would miss that little girl.

Libby finally reached the tumbler, and lassoed it expertly. She had done that same maneuver so many times now, she could do it with her eyes closed. In a way, that was a good thing, because it still gave her headaches to watch it spin.

Once she was inside the shack, Libby bounced over to the weblink, and logged in to her bank. Today was payday, and she wanted to make absolutely sure there would be no mistakes. She read the balance, twenty-two thousand seventy-eight dollars, and thirty cents. Just a hair over what she needed. It would be enough. She looked up from the weblink, at the fern she had potted against the door. A lamp was bolted above the winding plant, and a small fan blew air gently across it's leaves. Libby reached up and touched the base of the plant, checking to make sure the soil moisturizer was still working. The thin, wispy branches of the plant wound around her wrist slowly, as though trying to hold her. She frowned at that, and lightly shook them off. The plant wouldn't die here. Whoever they put in the shed next would want to keep it alive, if for no other reason than to cut down on oxygen costs.

Not that it would be much easier when she got home. She would have to start her life all over, building a career, finding a home. Mining the asteroid belt had taught her more about geology than most college graduates back on Earth, but it wouldn't seem that way to an employer. No, her experience among the stars wouldn't count for much of anything back home. She would have to work harder than others her age, just to prove her worth.

She rolled over, coiling herself in the hammock. Of course, the employment work would be on top of the physical therapy. She'd been out in zero G for too long. Even though she spent all her spare time at the Hail Mary with it's 1/3 G, she would still be in for a lot of straining when she got home. Going back to one Earth gravity would make her whole body weak and would strain her circulation badly. She wouldn't even be able to get up without blacking out for the first couple of days. Then there was the migraines that people got from lack of blood flow to the head. She'd have to spend a lot of time in the gym, on the treadmill, trying to get her muscles used to Earth again.

But it would all be worth it, just to get home. The important thing for her was that she get back to a normal life, where a person could earn an honest living, maybe have a chance for advancement. There was nothing out here for her. Just a dead-end job as a digger, days spent listening to her headset while carving up rocks, night spent waiting for her chance to go home.

Curled up in the hammock, she slowly fell asleep, and dreamed of Earth.

In the dream, she could see the blue of the sky above her, could feel the warmth of the sun. The wind blew past her face, sending ripples of joy through her. She could feel the cool grass beneath her feet.

But as she breathed it in, she could feel it all getting smaller. The sky started shrinking around her, clouds collapsing in on her. The sun shone down hot on her face, blinding her with it's light. As she raised a hand to her eyes, the wind ripped past her body, chilling her. She started to stumble backwards, but couldn't move. She looked down at her feet, and saw them encased in grass. The very ground was reaching up, with earthen hands, to grab at her shins and calves. She thought she saw tendrils of the fern's branches winding around her calves.

She looked around wildly, as the bubble of sky collapsed further in on her. The cloud cover was too thick now, so she couldn't see through the blinding glare of the fog around her. She crouched down and pulled at the grassy hands that grasped for her knees. She ripped at them, trying to free herself, as the bubble pulled in closer and closer. She screamed and found there was not enough sky for her to breathe.

Libby woke with a start, rolling herself up violently in the hammock. She wrestled her way out, and checked the time. Six hours. She ran a sweaty hand over her forehead and thought about changing clothes before she left. Then, as the groggy feeling left her, she shook her head violently, and started to pack.

Chapter 9

Half an hour later, she'd gathered together her meager pack of personal items, and was ready to leave. She looked around the tiny shack to see if she'd left anything. For over a year she had come back here to sleep, and it seemed strange to her that, after all this time, it still looked like it did when she first got there. The place was a little brighter (she'd put in a second light), a little cleaner (she'd worked hard on cleaning it in her first few months there), and she had bought the fern. But in essence, it was the same. There was no real sign that she'd ever been there.

Libby cycled the door and, crawling hand over hand along the outside of the rock, she found the bare patch where her name should go. She got a screwdriver out and touched the tip to the bare spot on the rock. She traced her name lightly on the loose sand that collected along the top, then got ready to make the deep cuts.

Somehow, she couldn't bring herself to do it. She stared at the bare patch for a moment, then with one violent motion, stabbed it with her screwdriver. She pulled herself over to the front of the shack, and got on the runabout. As she turned it on, the runabout radio started playing a bright, poppy tune through her suit. She switched off the radio, and looked around her. She suddenly realized that she didn't notice the spinning sky any more. It roiled and spun around her, a kaleidoscope of huge rocks in static constellations. But she knew the rocks now. She knew their names, and she was used to seeing them jump from one horizon to the other.

She left the shack unlocked. What was the point, after all? It would only be left for the next poor sucker, to be the butt of all their jokes. She didn't care. She wasn't the least bit worried about the next person dumb enough to follow this dream.

She noticed as she flew back to Blessed that it seemed like a quiet flight. Of course, with the radio turned off and the vacuum of space all around, it would seem quiet. Even considering that, though, it seemed odd to have nobody out working, traveling between rocks, loitering with friends. As she passed one homestead after another, she couldn't see a single person. Like the missionary said, it was quiet - too quiet.

As she reached the town bubble proper, she saw hundreds of runabouts tethered outside the loading port. In her whole time here, Libby had never seen a gathering this big. It would explain everyone missing from their work. Maybe they were having a big party. A parade or celebration. She had seen large gatherings out here before, for birthdays and weddings. Woody's birthday party had brought out almost everyone. That was a time to remember.

There were some good times out here, and she had pictures. She would carry those memories back when she went to Earth. It would help soften the year of living painfully.

As she cycled through the door, she encountered another shock. The mad press of people, going about their individual trades, was missing altogether. There were just a few people running from place to place, leaving the corridors as empty as she'd ever seen them.

Libby walked slowly toward the ticketing office, hearing the crunch of her own feet against the velcro ground. She marveled at the city, now that she could see it without interruption. It really was quite lovely, a testament to human engineering in concrete and steel. She hoisted her pack up on her shoulder and continued to the ticket station.

Her path led, as all paths do, past the Hail Mary, and she thought about poking her head in to say goodbye. As people passed her, some of them crowded into the doorway, unable to enter. Whatever the big party was, it was being held in the Mary. From inside, Miriam's booming voice called out, organizing something. Libby figured it would probably be best not to break up the party with her news, so she headed on.

The ticket station was basically an alcove dug into the rock, with a single desk set up in it held up by the filing cabinets underneath, and a weathered steel sign above it that read "S&V Travel Agent". Libby thought the travel agent's job might just be one of the cushiest in the city, given that there was only one destination, and only one price. The only way out of the asteroid belt was the S&V bus. It was a cargo ship that left once a month, and always had room for one more person. A person with twenty thousand dollars.

Now Libby was ready to become that person. She stepped up to the desk, and looked around. There wasn't anyone at the desk today. She saw, on the desk, a sign which read "Out to Lunch. Be back" A weather beaten clock was printed underneath, with a no hands to show the return time.

She waited there for a few minutes, thinking about heading back to the Mary. There were people she would want to say goodbye to. During the past year, Woody had always been kind and helpful to her. Little Dora had helped her enormously with her studying, and taught Libby everything she knew about geology. And of course, if it hadn't been for Miriam extending her credit from the beginning, Libby knew she would have surely starved. She shifted her weight impatiently from one foot to the other. Yeah, as difficult as it would be, there were a lot of people she should owed a goodbye to.

Suddenly, she noticed y

elling from the direction of the Hail Mary. The yelling sounded insistent, angry. She heard distant echoes of the shouts, "Come on!", "Let's get her!" She took one long, lingering look in that direction, seeing the people stream over to the Mary. That was no party. In her mind, she envisioned torches and pitchforks. What could make this group get so riled up and angry?

Libby grabbed an invoice off the desk, and flipped it over to write on the back. She scribbled, "When you get back, call me. I need to buy a ticket ASAP. -Libby Carter." She put the pen back in her pack, then stared at the note. Nobody called her Libby anymore. He wouldn't know who to call. She sighed, and pulled out the pen again. Under her name, she wrote, "Tumbler."

Libby shouldered her pack, and ran over to the Mary, pushing people out of her way. The Hail Mary was packed that night, standing room only. No one bothered to push the tables out of the way, they were just moved to the periphery as people pushed past them, and crowded around the bar.

Libby was a tiny woman, but living in cramped quarters with people who pushed and shoved their way all the time, Libby had learned how to walk with her elbows. She got admission the hard way, stepping on some feet, bruising some shins, climbing over a few people, and hanging on to a chandelier as she jumped from one person's shoulders to another. She pushed her way to the front, where everyone was gathered.

In the middle was Miriam, with a glare of anger, and holding her arms out like Moses dividing the seas. She was shouting, "Now calm down. Everybody just calm down. If you could just quiet down for a moment -"

They couldn't hear her. There was a general clamoring as people pushed around, tried to shout questions, tried to tell each other to shut up. Nobody was able to hear through their own consternation. Libby was about to start shouting for silence herself, when the report of a single shot rang through the room.

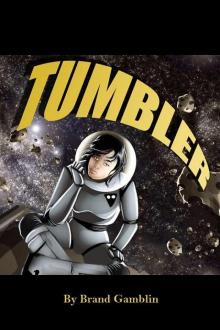

Tumbler

Tumbler